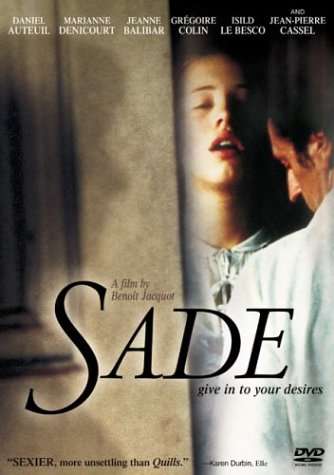

The Marquis de Sade in a More Complex Guise

Raving lunatic or subversive bad boy? Revolutionary intellectual or fiend from hell? The Marquis de Sade is such an inflammatory figure that when you contemplate his life, the imagination tends to run wild. But as embodied by the French actor Daniel Auteuil in ”Sade,” Benoît Jacquot’s smart, cool-headed costume drama, the marquis is a disturbingly recognizable figure: a sly, charming, ruthlessly arrogant bon vivant with a scary current of rage zipping like a live wire under his reptilian surface.

When Sade casts a hard, beady-eyed gaze on a virginal young woman, his expression is the cold, evaluative stare of a jaded predator. In his too-glittering eyes, you can almost read the graphic sexual scenarios dancing through his mind. Mr. Auteuil’s Sade, with his mixture of tense, coiled civility and ferocious willfulness, has almost nothing in common with the histrionic madman played by Geoffrey Rush in ”Quills.” Mr. Rush’s Sade, for all its high dramatic flourishes, conveniently excused the viewer from having to judge the Marquis. Because his character was so obviously crazy, he was not one of us.

Mr. Auteuil’s Sade is a much more complex and disquieting figure. He may be monstrously selfish, but he’s not out of his mind. As he flauntingly endorses what nowadays is called transgressive behavior, he bears some resemblance to the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe.

Contemptuous of Christianity and especially of Robespierre’s Cult of the Supreme Being, Mr. Auteuil’s Sade is a proud atheist and indomitable voluptuary who can barely conceal his contempt for the fools around him. His furtive bravado and reputation as a libertine lend him a personal magnetism that sets him apart from everyone else. Because he has special knowledge, open-minded (and especially young) people are drawn to him.

The movie, which opens today in Manhattan, has no pretensions to being a thorough biography. It is an intimate profile of Sade at a historical flash point. The year is 1794 and Sade, who is in his 50′s, is removed from the dungeonlike St.-Lazare prison and incarcerated with many other French aristocrats at Picpus, a former convent that has been turned into what today might be called a country-club prison. Since the residents must pay for their own room and board, only the well-to-do need apply.

Sade, an adept political manipulator, has wound up at Picpus through the machinations of his beautiful mistress Sensible (Marianne Denicourt) who is having an affair with puritanical (and sadistic) Fournier (Grégoire Colin), a member of Robespierre’s inner circle, who despises Sade but out of love for Sensible pulls strings to save him.

Life at Picpus is a surreal mixture of frivolity and terror. The residents cavort like spoiled courtiers, and Sade is permitted to stage a sadomasochistic tableau vivant set in a harem and depicting the ”joys of captivity.” At the same time, cart-loads of dead bodies keep arriving for burial in mass graves, and the accumulated corpses have left a terrible stench. The well-heeled prisoners all know they could be next on the death lists that are drawn up daily.

The story focuses on Sade’s tutelage of Emilie (Isild Le Besco), a viscount’s spirited, virginal daughter who, despite her parents’ warnings, discreetly cozies up to Sade and voices her desperate fear that she will die without ever having lived. The two play a coquettish game in which he advances and she flees but always returns a little bolder than before. Gradually, she learns to trust him, and he imparts his philosophy: There is no afterlife, and death is just a part of nature. Although Ms. Le Besco’s Emilie isn’t a live wire like Gwen, her character in ”Girls Can’t Swim,” which opened last week, the young actress gives a finely shaded portrait of adolescent rebellion in the 18th century.

Ultimately Sade arranges and supervises Emilie’s defloration by Augustin (Jalil Lespert), a handsome young gardener who is as shy as Emilie when the moment of consummation approaches. This complex, fairly explicit scene reveals more about Sade’s erotic imagination than anyone else’s. To fire up Augustin, Sade insists the gardener flog him severely. The remarkable scene is tinged with the self-punishing sadness of a middle-aged man who, despite his audacious sexual stage management, ends up gaping enviously from the sidelines.

In its quiet, literate way, the film is almost as subversive as its central character. As the Reign of Terror lifts, and the characters go their separate ways, Sade emerges as an almost heroic figure, whose careful nurturing has liberated Emilie to be herself. He has done a good deed.

Stephen Holden, NY Times, April 26, 2002

“http://keep2share.cc/file/52136f52a915b/Sade.mkv

http://rapidgator.net/file/6d48d5f35128f557921894b3796dac94/Sade.mkv.html

Language(s):French

Subtitles:English